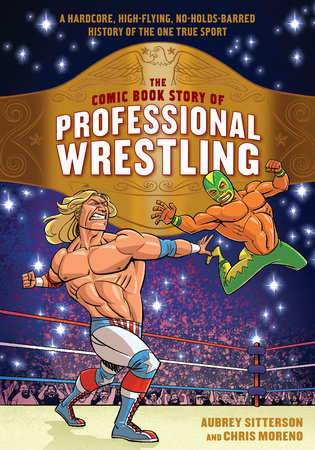

Sitterson, Aubrey and Chris Moreno. The Comic Book Story of Professional Wrestling: A Hardcore, High-flying, No-holds-barred History of the One True Sport. Ten Speed Graphic, 2018.

Review by Ben Abelson

The Comic Book Story of Professional Wrestling (from here on referred to as CBSPW), written by Aubrey Sitterson, and illustrated by Chris Moreno, is a fun, engaging, and amazingly comprehensive introduction to the history of pro wrestling that uses all the resources of the comic book medium to simultaneously inform and entertain the reader concerning its subject matter, which it both teasingly and affectionately refers to as “the one true sport.”

CBSPW is packed more densely than a forty-person battle royal with information, tracing wrestling from its antecedents in the Ancient world and formative beginnings in the nineteenth century American carnival circuit, all the way to the dynamic wrestling scene contemporary to the book’s publication in 2018. In addition to the grand sweep of time covered, CBSPW also spans the globe, with sustained treatments of wrestling’s development in Japan, the UK, and Latin America. Incredibly, the length and breadth of content included in the book does not come at the expense of depth, complexity, or precision. Most readers, whether seasoned fans, budding wrestling historians, or industry pros, will find something new and interesting within its pages.

Sitterson’s writing is lively and uncannily concise, making the book accessible to any reader regardless of their level of wrestling savvy, while simultaneously doing justice to the subtlety of the issues discussed in a way that should satisfy the most sophisticated student of the game. Moreno’s illustrations, too, strike an astonishing balance between conflicting priorities to achieve dual ends. They are explosively dynamic and evocative of the colorful, animated feeling of wrestling at its most exciting, while also rendering incredibly realistic and accurate likenesses of the dozens of distinct personalities represented.

The first two chapters are particularly fascinating as they delve into pro wrestling’s shadowy origins. Chapter One begins by tracing wrestling’s roots to the beginning of human history, citing mentions in Classical tomes steeped in myth, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Old Testament, as well as historical accounts of the wrestling of Ancient Greece practiced even by the philosopher Plato. It then details the development of what we would come to know as professional wrestling, which merged the rough and tumble fighting of the American colonies, the American catch-as-catch-can grappling style, and European “Greco-Roman” technique, with the spectacle and con-artistry in postbellum traveling carnival shows, yielding the hybrid discipline practiced by George Hackenschmidt and Frank Gotch in their legendary matches at the dawn of the twentieth century. Here, Sitterson introduces one of the main conceptual leitmotifs of the book, for which he will provide ample evidence in the history documented: the idea that the legitimacy of pro wrestling matches has always been in question and that there’s no definitive time when one can say matches began to be predetermined. Accompanying this notion is the fascinating meta-theatrical practice of “acknowledging the fixed nature of current wrestling as a way of romanticizing the reality of the past” (13), which informs individual wrestling characters and storylines in myriad ways. Sitterson elucidates, through frequent examples, how wrestling often trades on blurring the lines between reality and fantasy in ways that keep audiences guessing about what’s “real” and what isn’t.

Chapter Two covers the era when most of the conventions of pro wrestling were codified under the visionary direction of the “Gold Dust Trio.” They were the first promoters to intentionally eschew realism in favor of excitement in the ring, while at the same time maintaining some fully legitimate wrestlers in their stable, such as the Trio’s own Ed “Strangler” Lewis. “Hookers” like Lewis were needed protect the business from those seeking to take advantage of it, such as Stanislaus Zbyszko, who stole the World Heavyweight Championship in 1925 by “shooting” on his opponent. The chapter’s final page feature on “wrestling slang” includes a quick glossary of major terms which the uninitiated will likely find helpful.

Chapters Seven and Eight concern the rise of national pro wrestling companies and Vince McMahon’s eventual total domination of the industry in the 1980s and 90s, which Sitterson controversially attributes more to McMahon’s unyielding pursuit of excellence in cultivating and marketing his product than to his ruthless disregard of established convention, citing competitors’ unsuccessful bids for imperialistic expansion as evidence.

The final chapter deals with the new millennium, including McMahon’s purchase of his competition, the Guerrero and Benoit tragedies, the independent wrestling movement exemplified by upstart companies such as TNA and Ring of Honor, the “Women’s Revolution” with its genesis in WWE’s developmental brand NXT, and the creation of the WWE Network. Published in 2018, the volume cannot be faulted for being somewhat outdated. It refers to now defunct promotions, such as Chikara and Lucha Underground, as currently in operation, and it was written before the creation of All Elite Wrestling and the Covid 19 pandemic, both of which have subsequently transformed the wrestling landscape.

In the end, Sitterson, having presented a persuasive argument through various examples over the course of the book, reiterates what he takes to be the two fundamental characteristics responsible for wrestling’s enduring popularity: 1) blurring of the line between fact and fiction, and 2) the primal immediacy of a violent morality play.

One limitation of CBSPW that some critical readers might find unsatisfactory, is that it does not offer sustained discussion of what may be viewed as wrestling’s more “problematic” aspects, including its history of misogyny, racism, and homophobia, as well as its generally exploitative treatment of workers. These flaws are not completely ignored in the book — they are briefly addressed — but the general tone of the book is one of celebration not critique. For instance, Sitterson admits that not much space in the volume is devoted to women’s wrestling. On my tally, references to women in the book total about three total pages out of the book’s one hundred and seventy. The pages include: slightly more than a single panel in Chapter Three discussing pioneering women, such as Mildred Burke and Fabulous Moolah, and also “midget wrestling”; a little over a page in Chapter Six about “Joshi” wrestling in Japan; three panels in Chapter Eight — depicting Madusa throwing the WWF Women’s Championship in the trash, showing Beulah McGullicutty rolling around the ring erotically with Kimona Wanalaya in ECW, and illustrating Lita tearing off Trish Stratus’s clothes. Chapter Nine offers a page covering the “Women’s Revolution.” Sitterson partially attributes this lack of representation to women’s historical diminution by the business, but readers might find this excuse less than satisfying. Similarly, the one-page feature on ethnic stereotypes and caricature at the end of Chapter Seven, along with a few other scattered remarks, only scratches the surface of wrestling’s xenophobic history, and the provocative “burlesque for boys” feature closing out Chapter Eight raises more questions than it answers about the roles that gender identity and sexuality play in the psyches of both wrestling producers and consumers.

Overall, readers should find CBSPW a valuable addition to their libraries — a handy quick reference for major formative events and persistent themes in wrestling history that is both illuminating and enjoyable.

Ben Abelson is Associate Professor at Mercy College and co-host of the Contesting Wrestling podcast. You can read more about Ben’s work here.